By Will Hornblower

Across the Oak Grove campus, parents and staff have been discussing strategies to improve the way that adults connect and communicate with children. Over the course of three workshops, we brainstormed ways to help students develop resilience, autonomy, and rapport with adults.

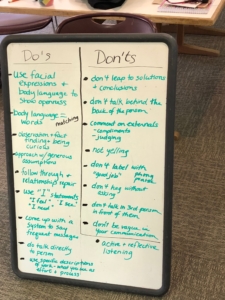

We started by posing a question to a gathering of the entire Oak Grove School staff and teachers: How should we talk to students at Oak Grove? This evolved into the obvious counterpoint: How shouldn’t we talk to students at Oak Grove? The teachers generated some excellent strategies. Here are some that might be of benefit in the home:

“The do’s” of adult-child communication:

Faculty and staff generated some “Do’s and Don’t’s” on how we communicate with children on campus.

- Body language equals words: show children that you are giving them your full attention by engaging in active listening. Here is a link to some active listening advice for those interested in practicing at home.

- Use “I” messages to communicate your feelings. Communicate your feelings honestly, and encourage children to communicate their feelings using “I messages” as well.

- When praising a child, praise the process and not the person or result. Instead of saying, “You are so good at math!“, try saying, “I like the way you tried all kinds of strategies on that math problem until you finally got it.” Here is more information on recent research on the effects of different types of praise in encouraging a growth mindset.

“The do not’s” of adult-child communication:

- Avoid making assumptions or leaping to conclusions when communicating with children. Often, we are only projecting our own anxiety onto the child. In her wonderful book, Peaceful Parent, Happy Kids, Dr. Laura Markham writes: “When we are worried, we usually feel an urgent need to take action. That alleviates our own anxiety but doesn’t necessarily give the child what he needs. So the first intervention is always becoming aware of and regulating our own emotions.”

- Avoid comparisons when your child is within earshot, especially comparisons to siblings. Kids are always interested in what adults have to say about them, and this can shape their own feelings of self-worth.

Strategies for Elementary Students

Every time you talk to a child you are adding a brick to define the relationship that is being built between the two of you. And each message says something to the child about what you think of him. He gradually builds up a picture of how you perceive him as a person. Talk can be constructive to the child and to the relationship or it can be destructive. – Thomas Gordon

Our first parent education workshop discussed communication strategies for younger students to help them develop resilience, autonomy, and executive function. Here are some strategies that we came up with:

Routines and rituals that help to encourage connection and communication:

- Regularly scheduled family meals. Assigned chores and structured conversations help make these meals more successful.

- An unhurried bedtime routine. Build plenty of space into your bedtime routines for conversation and connection while still making sure that your child enjoys the health benefits of adequate sleep.

- Structured daily reflection activities like: “Rose, Thorn, Bud” or “Three Good Things.”

- Screen-Free Sunday (or Saturday) for all family members. If you really want to go big, try a screen-free week.

- Enjoying nature together

Calming your child during moments of extreme anxiety or agitation:

- Soothing experiences like baths, massage, or snuggles.

- Role play and storytelling.

- Creating safe spaces and providing stress-relieving toys and objects for children.

- Mindfulness routines

- Modeling self-regulation by taming your own emotions during high-stress moments.

Strategies to use when your child is struggling with his/her social or academic life:

- Coaching, not controlling: consider the consultant model over a more authoritarian approach. Instead of offering solutions, ask, “How can I support you?”

- Asking specific questions about academic or social life as opposed to more general questions.

- Avoid power struggles around homework

Here are some helpful resources that we distributed during the workshop:

- Refrigerator sheet- How to Talk So Kids Will Listen And Listen So Kids Will Talk

- Executive-Function-Activities-for-7-to-12-year-olds

- Whole Brain Child Refrigerator Sheet

- Dr. Laura Markham- Gameplan for Parenting Your Elementary Schooler

Strategies for Secondary Students

As parents, our need is to be needed; as teenagers their need is not to need us. This conflict is real; we experience it daily as we help those we love become independent of us. – Dr. Haim G. Ginott

Our second parent education workshop discussed communication strategies for older students to help them retain healthy attachments and strong connections with their parents and caregivers:

Routines and rituals that help to encourage connection and communication:

- Electronics-free times such as meals or even encouraging an entire screen-free day.

- Sharing common interests and hobbies: sometimes conversations flow better when engaged in a common task like cooking, hiking, or surfing.

- Game nights and playing music together.

- Going out on a one-on-one “date night.”

- Being enthusiastic at child’s sports and performance events.

Approaching difficult conversations such as discussions on sex, substance abuse, or peer conflict

- Using facts and discussing current research as opposed to voicing opinions. A calm demeanor and positive body language also help to avoid activating a child’s defense response.

- Using movies, tv shows, or current events as teachable moments or to discuss sensitive issues.

- Talking about issues in abstract terms or using another person’s experience as opposed to asking personal questions.

- Do not make assumptions about your child’s views on alcohol, sex, or other sensitive topics.

- Have a plan for when your child asks you about your own teenage experiences.

- Choose your moment to have a conversation; don’t “ambush” your child with a difficult conversation.

Strategies around electronics use to avoid miscommunication and to promote connection

- A media contract is a useful negotiating tool to remind parents and children about expectations.

- Modeling responsible media use is important as children observe and criticize every action by adults that might be deemed hypocritical.

- Texting and email can create misunderstandings. Convey important information in a face-to-face interaction.

Here are some helpful resources that we distributed during the workshop:

- Tips For Talking To Your Child About Sex, Drugs and Alcohol

- Communication Blocks to Avoid

- Why Your Grumpy Teenager Doesn’t Want to Talk to You – The New York Times

- 30 Ways To Stay Connected With Your Teen

Here is a link to a schedule of our upcoming parent education workshops.

Thank you to those of you who were able to attend our Parent Education workshop on implementing Growth Mindset practices in your household. It was wonderful to see such a dedicated group of parents working together to discuss what actions and language will best help their children to embrace a culture of effort and perseverance.

Thank you to those of you who were able to attend our Parent Education workshop on implementing Growth Mindset practices in your household. It was wonderful to see such a dedicated group of parents working together to discuss what actions and language will best help their children to embrace a culture of effort and perseverance.